In the past year, most parts of the country have seen median advertised rent prices on realestate.com.au rising in the order of 10%.

With rents growing so quickly, there have been concerns expressed that the Reserve Bank is worsening the rental crisis, by hiking interest rates by 3.5 percentage points in less than a year.

Landlords are facing substantially higher mortgage costs, and that’s forcing them to raise rents – or so the argument goes.

RBA governor Philip Lowe has been reluctant to accept that criticism. In his recent appearance before the Standing Committee on Economics, he had this to say:

“The critical issue here is the lack of rental accommodation. That’s what’s driving higher rents, not higher interest rates.”

He has good reasons to say this.

The simple version of economic theory doesn’t support a link from interest rates to rents. And, more importantly, the data doesn’t either.

Changes in interest rates and national-level rents shows no systematic relationship. Nor is there a relationship at the level of an individual rental property when we compare rent increase for rentals with and without a mortgage.

Soaring rates have been blamed for rapidly rising rental prices. Is that fair? Picture: Getty

Instead, the reason rents are rising so rapidly is that rental markets are extremely tight – there just aren’t enough rentals for everyone that wants to rent.

In theory, higher interest rates lower home prices – they don’t raise rents

In theory, higher interest rates don’t affect the current supply of rental homes, nor the number of people looking for rentals.

Interest rates don’t (in theory) directly impact rents. Instead, interest rates affect home prices – which is what we are seeing at the moment. Home prices have fallen as interest rates have risen.

Interest rates can matter for rents, but only in the longer run. Higher interest rates can reduce how many homes are built, which will lower the supply of housing. But this effect takes time – around four years.

To be clear: these are intentionally simple frameworks and deliberately abstract away many important real-world details in order to focus on core concepts and mechanisms.

Maybe those simplifications matter. Maybe, in reality, higher interest rates do in fact drive higher rents through some other mechanism these models don’t capture.

So instead, let’s look at the data.

At a national level, there’s no relationship between an increase in the cash rate and higher rents

The simplest way to look at whether rates raise rents is: what happens to national average rents when the RBA raises interest rates, on average?

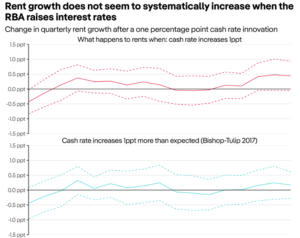

The top panel of the chart below shows exactly that.

The answer: not much.

There is no consistent, systematic relationship between increases in interest rates and rent growth.

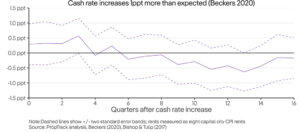

There’s a variety of reasons that this approach is very flawed, which we can discuss in the footnote. The bottom two panels show two better alternatives, that look at what happens to rents after the RBA raises rates by “more than expected”.

These alternative approaches do not change the picture: there is no evidence of a systematic response of rent growth to increases in the cash rate.

When we look at individual rentals, there’s also no evidence higher mortgage costs lead to higher rents

The macroeconomic evidence doesn’t support the higher-mortgage-rates-to-higher-rents hypothesis. But the macro evidence is far from conclusive in my view – there’s always lots of things happening to the economy, and that makes it hard to pick out a single mechanism like this.

So, let’s look at this question at the level of an individual rental property.

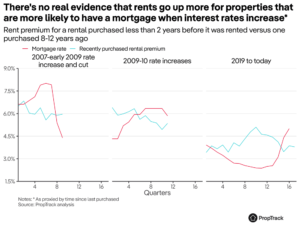

If landlords with loans pass on rate increase to tenants, we should find that properties with a mortgage have bigger increases in rent than properties without a mortgage when the cash rate increases.

Unfortunately, we don’t know whether a given rental property has a mortgage or not. But we do know how long ago a rental property was last purchased. And if we assume that more recent purchases probably, on average, are more likely to be mortgaged or have larger outstanding balances, we can use “time since last purchased” as a proxy for “has a mortgage”.

If higher mortgage rates cause higher rents, then the “premium” for newly bought properties versus older properties (ie properties with a mortgage versus those without) should systematically vary with interest rates.

The answer: there’s no evidence that rents for mortgaged properties increase by more than rents unmortgaged properties when interest rates go up.

The rental premium for a recently purchased property (ie how much more a recently purchased properties rents for) sat unchanged at 6% during 2007-2008, despite interest rates increasing rapidly. Nor did the premium fall in late 2008/early 2009 when rates were subsequently quickly cut.

The premium was again unchanged during the rate increases of late 2009 through 2010.

And during the pandemic, when rates were cut, the premium increased, and has decreased recently despite mortgage rates rising very quickly in 2022 and into 2023.

All of this is counter to what we would expect to see if more-heavily mortgaged properties increased their rents when interest rates increased.

The only counter example is that the premium for recently purchased properties declined very slowly between 2010 and 2015 alongside a decline in mortgage rates from 2011-2016. But this is a slow adjustment, and is probably a structural rather than cyclical change.

So… why are rents going up?

If theory, macro evidence, and micro evidence all refute the idea that mortgage rates systematically increase rents, why are rents going up so quickly right now?

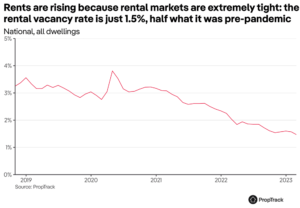

Simply: there aren’t enough rentals.

The rental vacancy rate – which measures the number of currently available rentals as a share of the total number of rental homes in Australia – is sitting at just 1.5% nationally. That’s around half what it was pre-pandemic. That means rentals are hard to find, and competition for them is fierce when they come up.

With rental markets this tight, rents would be rising no matter what happened to interest rates.

There’s no doubt that some landlords are using higher mortgage rates to justify raising rents. But it’s just that: a justification. If rental markets weren’t so tight, landlords wouldn’t be able to pass through those costs.

Calling on the RBA to solve the rental crisis by cutting interest rates is not the right solution.

Solving the rental crisis isn’t about lower interest rates, it’s about having more rentals. That means encouraging new investors in, and – longer-term – building more homes.

[1] In the short-run, higher interest rates actually lower rents in this models because higher interest rates slow the economy (ie increase unemployment). That lowers people’s willingness or ability to pay for rentals. For some examples of these models in an Australian context see: Saunders and Tulip (2019) and Ballantyne et al (2019).

[2] For instance, arbitrage transaction costs are ignored (these are large and likely important); landlords are assumed to be price-takers (this is clearly untrue – landlords have some degree of monopolistic power); and so on. These frictions could, plausibly, create a causal link from higher interest rates to rents.

[3] Chart shows the impact of a one percentage point increase in the cash rate, estimated using the local projections method from Jorda (2005).

[4] The main concern is that interest rates move in anticipation of economic developments and those could affect rents, or similarly, that interest rates and rents are both being driven by other variables (eg unemployment, which we are not accounting for). The former of these is often referred to as the price puzzle (se, eg, Romer and Romer (2004), or an Australian version in Bishop and Tulip (2017)). The shock series I subsequently use do not full address this concern as they are conditioned on forecasts for inflation, GDP and unemployment, not rents.

[5] I estimate this “premium” in a simple hedonic regression framework, where I regress advertised rents on key characteristics of the rental (property type and bedrooms, as well as location) and the time since the property was last purchased (relative to when it is advertised for rent). I run this regression for each quarter since 2007 to get an estimate of the premium for recently purchased rental properties over time.

[6] To be more precise: the correlation between changes in mortgage rates and changes in the premium for recently purchased problem is actually slightly negative, though it is very close to zero and is not statistically different from zero.

[7] Much of the increase in the premium during the pandemic was driven by an increase in the premium for very-recently purchased rentals (ie <1 year). The broad results are robust to removing this group and comparing the premium for 1-3 year old purchases instead of <2 year purchases – this rent premium for this group also shows no relationship with mortgage rates.

[8] The only argument in the favour of the “mortgage rates raise rents” is that both the premium on recent purchases and mortgage rates fell over the roughly five year period between 2011 and 2016. But this was a slow adjustment, the premium started declining before mortgage rates. So my interpretation is this an coincidental change, not a causal one.

Source: Realestate.com.au