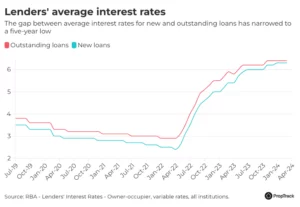

New and existing home loan customers are now paying almost the same interest rates, with the difference shrinking to the smallest it’s been in the past five years.

Since the start of the year, the average interest rate for new loans has been just 0.1 percentage point lower than for existing loans, according to the Reserve Bank.

Lenders typically offer new customers a better deal than existing customers in the hope of attracting new clients, but the data shows that the discount new customers get has reduced.

The difference between the rates new and existing customers pay is often referred to as the ‘loyalty tax’, with the idea being that customers who stay loyal to their bank pay more, while those that shop around are rewarded with lower prices.

But with profit margins under pressure, banks have become more focused on holding onto existing customers than attracting new ones, offering competitive rates and even matching introductory rates typically reserved for new customers in order to retain borrowers.

The size of the loyalty tax grew through the beginning of the rate rise cycle, when lenders sought to attract new customers either rolling off a fixed-term mortgage or seeking out a better deal.

The gap between rates for new and outstanding loans stretched out to 0.51 of a percentage point in late 2022, after the RBA had hit borrowers with four back-to-back double-sized rate hikes.

But as the frequency and magnitude of cash rate rises tapered off over 2023, the gap reduced, reaching a five-year low of 0.09 of a percentage point in February this year.

Mortgage wars ease as banks focus on profitability

This narrowing gap reflects an easing in the mortgage wars, according to AMP head of investment strategy and chief economist Shane Oliver.

“We go through phases where the mortgage market becomes highly competitive,” he told realestate.com.au. “Then banks pull back because it adversely affects their margins. That sometimes comes at the pressure of shareholders.”

“I think the reason for the narrowing is there’s been a diminishment in the quest for market share and a refocus of banks on net interest margins.”

The big four banks reported declines in net interest margins in half-yearly results this month, caused by strong competition for housing lending.

All four big banks reported shrinking net interest margins in their half-year results earlier this month, attributing the decline to strong competition for housing lending.

The net interest margin is a key measure of profitability comparing a bank’s funding costs with interest charged on loans.

NAB chief financial officer Nathan Goonan said the decline in net interest margins had slowed as pressure from competition in the lending market had moderated, but noted home lending was still expected to remain highly competitive.

Since May 2022, the cash rate has increased by 425 basis points, while the average interest rate for outstanding loans rose 353 basis points compared with a 387 basis point increase for new loans, according to the RBA.

Average interest rates paid by borrowers have increased by less than the increase to the cash rate since May 2022. Picture: Getty

Mortgage Choice broker David Thurmond said the smaller increase to rates for outstanding loans showed lenders were trying to hold onto existing customers who are increasingly shopping around.

“Right now it’s harder for banks to write new loans because borrowing capacities are so tight,” he told realestate.com.au.

“The banks are being a lot more aggressive in retaining existing clients.”

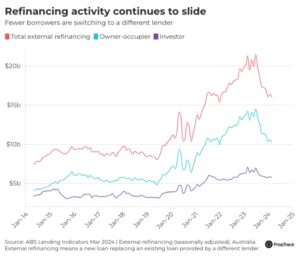

Refinancing declines but remains elevated

Refinancing activity peaked in July last year, when the total volume of refinancing reached almost $21.5 billion, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

This peak in refinancing coincided with the height of the ‘fixed rate cliff’, with hundreds of thousands of borrowers rolled off expiring fixed rates onto higher variable rates and many shopping around for a better deal.

Refinancing has fallen significantly since then, with about $16 billion worth of loans refinanced in March this year – about 25% less than a year earlier.

Mr Oliver said the decline in refinancing activity from the peaks of last year reflected the fact that many borrowers had already negotiated discounts with their lenders, making refinancing less viable.

“It gets harder to refinance with someone else because you’re already paying a lower rate,” he said.

Despite the decline in activity over the past year, a higher proportion of borrowers are still refinancing than before the current rate tightening cycle, PropTrack senior economist Paul Ryan said.

“Refinancing is still at very high levels, as people continue to move off fixed rates and respond to changing interest rates,” he said.

Mr Thurmond said the steepest rate tightening cycle on record meant borrowers were more conscious than ever about how much their loan was costing them.

“Because we’ve had two years of contestant increases and almost daily barrage in the press of inflation and potential rate rises, everyone is uber aware of where they sit,” he said.

“It’s not like the past where you could afford to set and forget. People are that much more sensitive to the higher rates so they’re reaching out.”

Complacency still has a cost

Mr Oliver said lenders’ focus on retaining existing customers meant borrowers who put pressure on their bank could potentially access a lower interest rate.

“Loyalty tax is still as much of a thing as ever and people need to be aware of it,” he said. “It relies on customers being more accepting and not particularly vigilant.”

“The bank is unlikely to change the rate they charge you unless you put pressure on them, at least with a phone call and maybe threat to go somewhere else.”

“It’s only when you question your loyalty that they act. Otherwise they continue to rely on your loyalty.”

Mr Thurmond said some borrowers would have success negotiating a small rate reduction by telling their lender they were shopping around for a better deal.

“But to get the big discounts, you need to go through the refinance process and trigger their retention team,” he said.

Refinancing is still an option for many, he said, but borrowers would need to secure an interest rate low enough for the savings to outweigh the fees of switching, which could range between $700 and $1000.

“You’ve got discharge fees, title fees and registration fees, so I need to prove at least in the first year that we’re going to cover those fees,” he said.

With household cash flow under pressure, Mr Thurmond said switching to a lower interest rate wasn’t the only solution, especially when switching lenders doesn’t stack up.

“We’re doing debt consolidation, or extending loan terms from 20 years to 30 years so people have a smaller required repayment.”

“Even though the interest rate might be the same, we’re saving them on cash flow.”

In some cases, rising property values could mean borrowers with more equity and a lower loan-to-value ratio could access lower interest rates, but stressed that expert help was likely to yield a better result than a DIY approach.

“The market is so complicated that you need someone with experience to have a chat with you and say ‘the rate you’re on with your existing bank is fantastic, stay there’ or ‘the grass is always greener’.”

Source: realestate.com.au