While we need more homes, data on planned development in our major cities shows they are not being prioritised where people want to live.

Current challenges for developers and planning rules are key impediments for growing our cities in these locations. But there is also significant well-located spare housing, that policy changes could unlock.

There is a focus on building more homes, but we also need to prioritise putting them in the right places

As rents and mortgage costs have increased over the past year, there has been a focus on increasing housing supply to alleviate housing shortages across the country.

The most visible of these has been the Government Housing Accord, which commits to building one million new homes over the next five years.

But where will they be built? If currently planned development is any guide – these homes will not be in the right places.

Solutions to the housing shortage should focus on building close to our major cities where people want to live, where prices are highest, and services are plentiful, as well as policies to better use existing well-located homes.

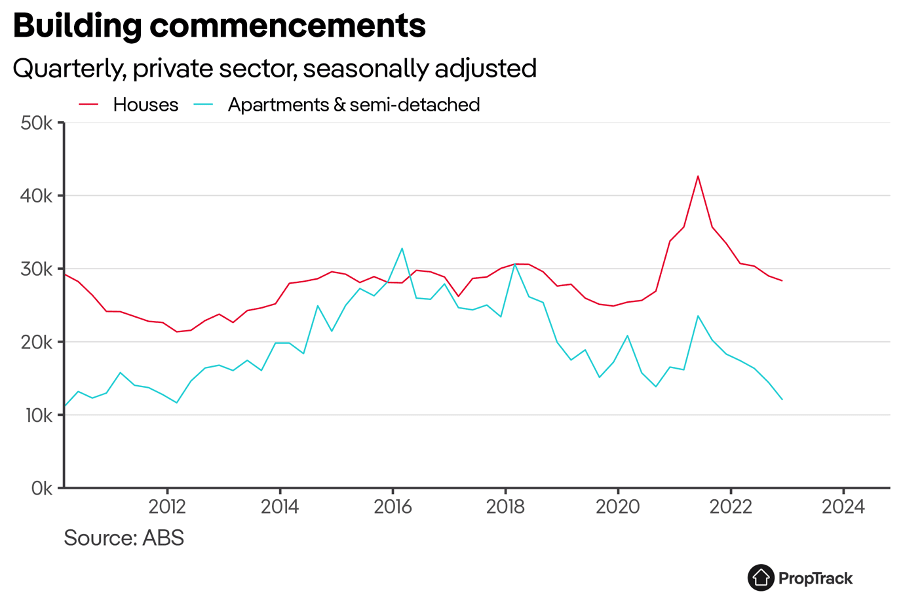

The pandemic began a series of disruptions which have limited construction of units and townhouses

The pandemic significantly impacted the building industry. Recognising this, support for the building industry was a key government response to the pandemic. HomeBuilder provided grants for the construction of new homes and renovations, and state governments also provided incentives to build and buy homes.

But these policies mainly benefited new house construction, mostly in new suburbs on the edges of our large cities.

By contrast, high-density unit and townhouse construction barely saw a boost through the pandemic. These homes are generally well-located, in high value areas close to services, but take many years to plan and construct.

These high-density projects were beset by uncertainty about housing demand, financing and the state of the economy throughout the pandemic. Tradespeople and other resources were also diverted to house and infrastructure construction elsewhere.

In total, 120,000 fewer homes – almost all units and townhouses – were built throughout the pandemic than construction rates from 2016-2019 would have produced.

As the economy recovered from the pandemic, new unit and townhouse construction has continued to fall.

New challenges have emerged for project developers. Supply disruptions from the war in Ukraine, and lockdowns in China mean material costs have increased considerably; tradespeople remain scarce; and higher interest rates have perpetuated project financing difficulties.

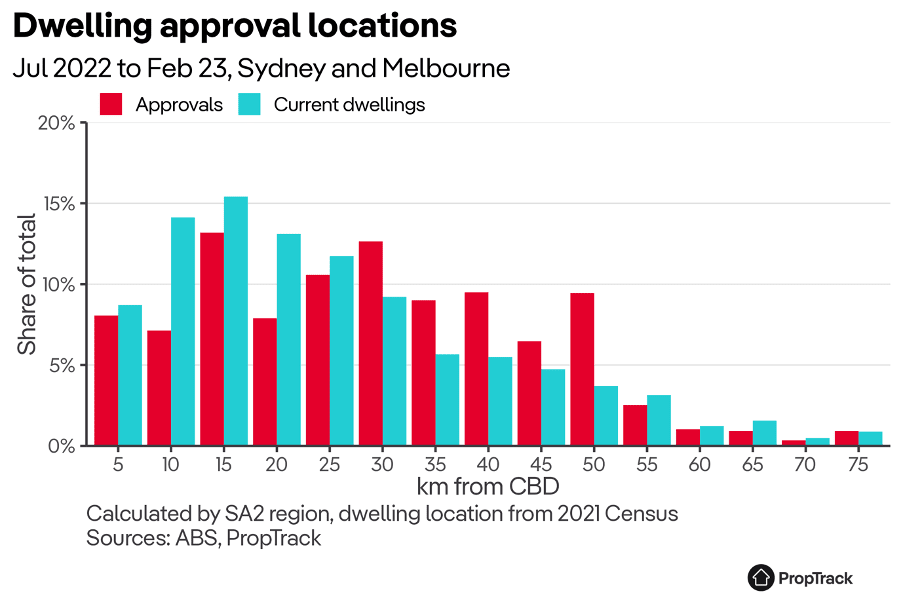

Homes are not being built where people value them the most

These challenges for unit and townhouse developers mean planned homes do not line up with where people want them the most.

Land values are highest close to major cities, where services are plentiful and commutes are short. But very little planned development is in these high-value locations.

In Sydney and Melbourne, where 40% of Australians live, a large share of homes approved to be built are 30 to 50 kilometres from the CBD. This pushes people further away from jobs, services and transport infrastructure.

Recent work by the NSW Productivity Commission and Peter Tulip at The Center for Independent Studies has shown that in inner Sydney, new homes are much more expensive than their cost of construction. Allowing more homes where values are highest would also lower the cost of housing.

It is clear that zoning and planning processes, which mean the approval process for new projects can take years, are a key impediment to building more homes where people want to live.

Inner-city homes are already overcrowded

The issue is more urgent than just housing new residents.

Homes in inner-city Sydney and Melbourne already don’t have enough space to house current residents.

In the 2021 Census, the ABS calculated there were 178,000 more bedrooms needed by households in Sydney and Melbourne – predominantly in homes close to the CBD.

Building where people want to live would also provide more housing where shortages are greatest.

But there is already unused housing where people want to live

The good news is we already have a lot of spare housing in well-located areas.

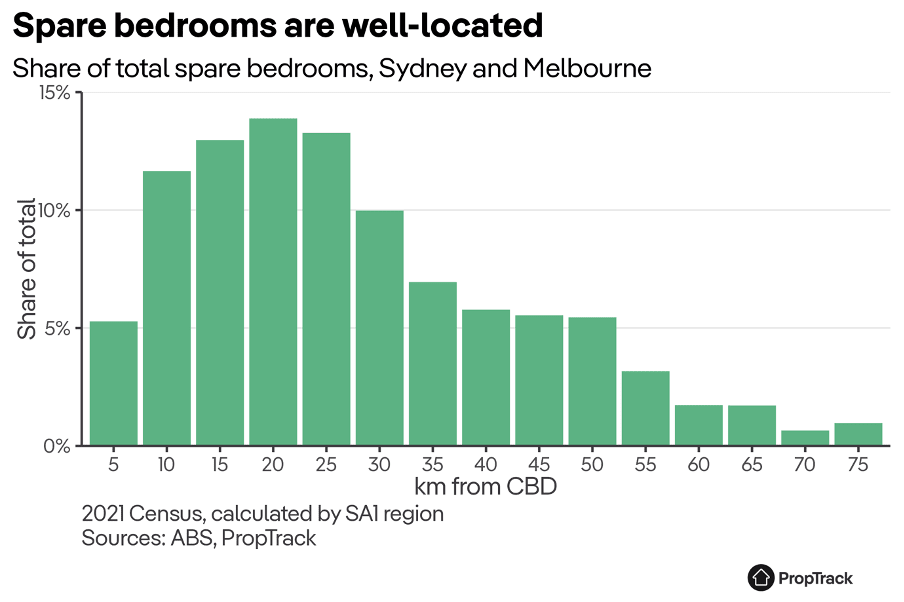

In Sydney and Melbourne alone, 1.28 million homes have more than one spare bedroom. These spare bedrooms are also predominantly located 10 to 30 kilometres from the CBD – where people need housing the most – and are most willing to pay for it.

Spare bedrooms are a reasonable luxury for many people. But policies that incentivise people to downsize into more appropriate housing and unlock larger homes for growing families should be encouraged rather than penalised.

The solutions are clear

A key reason housing is not being provided where it is demanded are restrictive planning and heritage rules, which make new development difficult and costly. They also only give current residents a voice in development decisions, at the exclusion of those who would benefit from more homes.

With higher housing costs, these limitations are getting more attention.

The NSW state government has proposed large developments circumvent them completely in return for allocating 15% of their projects to affordable housing.

Other policies, and coordination, are also needed to alleviate the challenges the construction industry is facing, so projects can be commenced as soon as possible.

Policy changes can also unlock the housing we already have. Moving away from stamp duties which penalise moving, to broader land taxes that incentivise people to live in homes that best suit their current circumstances has big benefits and doesn’t require any new development. Current exemptions for the family home in pension asset tests also discourage many from moving.

The solution to the current housing crisis is a combination of allowing more homes where people want to live and policies that encourage better use of the homes we have.

Source: Realestate.com.au