ANALYSIS: Amid a national rental crisis, fast recovering population growth, and constrained housing supply, measures to address the housing shortage and worsening affordability featured prominently in this year’s budget.

While renting is a vital part of Australia’s housing market, it has been failing many.

Nationally, advertised rents have soared 11% year-on-year, and vacancy rates are at historic lows. With the outlook remaining challenged, the budget’s new housing line items honed in on this area.

Increased assistance payments for low-income renters, measures to boost rental supply and measures to increase construction of social and affordable rental housing are the big-ticket items.

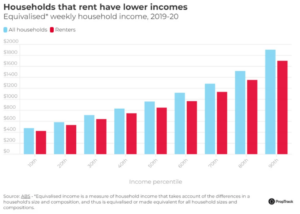

Given the one in three households that rent are more likely to be younger Australians, on lower incomes, with less wealth than owner-occupiers, and typically lower savings buffers, the measures will come as some relief.

Commonwealth Rent Assistance increases

Commonwealth Rent Assistance is already available to Australians on pensions and benefits including JobSeeker, the Family Tax Benefit and Parenting Payment.

The budget has delivered funding to increase the maximum rates of the Commonwealth Rent Assistance payment by 15% in a bid to help ease pressures on low-income renters.

The maximum increase will be between $15.73 and $31.76 a fortnight.

Renters currently receiving Commonwealth Rent Assistance will receive up to $31 extra a fortnight from September, a measure aimed at assisting vulnerable lower-income renters. For most low-income earners, rent assistance is a targeted and cost-effective safety net.

Strong demand to rent, bolstered by the fast pace of immigration, is well outstripping the supply of available rentals, with the total supply of rentals in the capital cities sitting at historic lows in March, with the supply of available rentals down 18.3% year-on-year.

Meanwhile advertised rents in the capital cities increased by 13% over the year to March with the extreme shortage of rental stock weighing.

This increase to Commonwealth Rent Assistance is the largest in more than 30 years, but rent assistance payments have long fallen behind soaring rental prices.

In the capital cities rental prices are up 18% on pre-pandemic levels, while in regional areas rents are up 23%.

Capital city rental markets are significantly undersupplied. As a result, prices are rising briskly and vacancy rates trending lower.

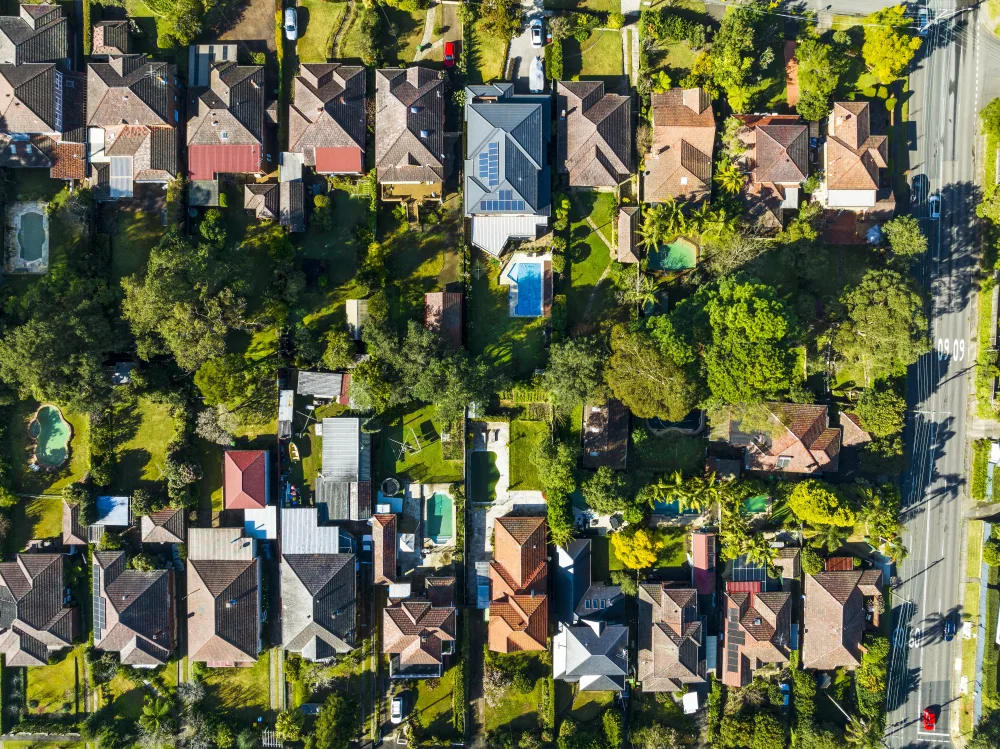

Rental prices are rising across the country amid low supply and high demand. Picture: Chris Pavlich.

Pegging payments to adjust in line with subsequent market rental price increases in the future, or a regular review schedule to ensure that assistance payments keep pace with surging rents, could have been a welcome step further.

The persistent undersupply of properties available to rent is pushing vacancy rates lower. And with rental demand outstripping supply, weekly rents are increasing strongly. And without a meaningful increase in rental supply on the horizon rental prices will continue to grow in the coming months.

But rental price increases aren’t the only problem. These challenges don’t just manifest in budgetary constraints as weekly rents increase, but with fierce competition properties are renting out at record speeds and finding an available rental is tough. The level of competition for limited rentals is forcing many to make sacrifices.

In the long run, the best solution is to provide more dwellings, but this takes time.

New tax break for build-to-rent sector

The only sustainable solution to the rental crisis is increasing rental supply.

Building approvals have fallen sharply over the past year are now sitting at decade lows, led by a significant 46% year-on-year drop in approvals for private sector apartments, especially larger builds.

Industry challenges, higher construction costs and labour shortages are set to see growth in the supply of new rentals remain limited, at a time when there is already a severe shortage of available rentals.

This is a problem; the supply side of the housing market should be better able to adjust when needed.

An increase to the available pool of long-term rentals could come from increased activity from both small and large-scale investment.

Last year’s budget announcement, the Housing Accord aims to build one million, new, well-located homes over 5 years from 2024.

This budget aims to help achieve this by incentivising an increase in the supply of rental housing by reducing barriers to entry and tax disincentives for large scale investment via the build-to-rent sector.

Treasurer Jim Chalmers has handed down his second budget. Picture: NCA NewsWire/ Dylan Robinson

Build-to-rent is a real estate development model where a property is constructed specifically for the purpose of renting it out, often with long-term leases and professional property management.

This sector could play a helpful role in alleviating rental supply constraints.

The withholding tax rate will be cut from 30% to 15% for eligible fund payments from managed investment trusts to foreign residents on income from newly constructed residential build-to-rent properties after 1 July 2024, subject to further consultation on eligibility criteria.

The depreciation rate will rise from 2.5% to 4% per year on eligible new build-to-rent projects where construction starts after May 9, increasing the after-tax returns for build-to-rent developments.

Build-to-rent dwellings must also offer a lease term of at least 3 years for each dwelling, meaning a predictable income stream for developers but also stable longer-term tenure for tenants.

While encouraging increased investment and construction of build-to-rent projects won’t help with the current pressures and low supply of rentals, advancing the build-to-rent sector could help increase rental supply in the long term.

But is it enough to move the dial?

The budget states industry estimates that cutting taxes on build-to-rent developments could lead to an increase of 150,000 new rental properties over the next 10 years.

150,000 additional rental properties would be a just over 6% increase to our current total rental stock over the next decade.

In the year to September 2022 the population swelled by a record 418,500 people, driven by net overseas migration of more than 300,000 people in the same period, a near record. In fact, Australia experienced the largest quarterly net inflow of overseas migrants on record in the September quarter at 106,000 people.

Treasury estimates there will be an influx of 715,000 migrants over the course of this financial year and next.

Based on ABS household projections out to 2033, 150,000 new rentals will cover just 9.6% of the forecast increase in the number of households.

Meaning with the faster than expected return of immigration and strongly rebounding population growth, 150,000 additional rental properties in a decade will aid rental supply shortages but probably won’t provide enough of an increase.

Build-to-rent is already an established asset class in the US, Europe, and Japan and could be a key missing ingredient to the housing mix in Australia.

Encouraging smaller investors to return to the market is a missing ingredient in today’s budget.

Although advancing the build-to-rent sector is a welcome measure, policy that aims to incentivise small scale investment via “mum and dad” into the housing market thus adding to rental supply appears to be missing.

Social and affordable housing

The government also announced an extra $2 billion to lower the cost of construction of social and affordable dwellings.

The additional $2 billion is set to increase the National Housing Finance and Investment Corporation’s (NHFIC) liability cap from $5.5 billion to $7.5 billion from 1 July 2023, which will enable the NHFIC to support more social and affordable rental homes through lower cost loans to community housing providers.

The increased funding for social and affordable housing will help provide stable and secure housing options for those who need it, but while social housing is a good safety net for those at high risk of long-term homelessness who can’t access private housing, it is an expensive solution.

The additional billions are expected to support around 7,000 more new social and affordable dwellings, a step in the right direction, but the impending increases to rental assistance will be a better targeted measure.

What’s ahead for the rental market?

Strong rent growth is likely to persist this year. This is particularly the case in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane, where most arrivals first land and rental supply is tight. Adelaide and Perth also have very constrained supply conditions.

However, renters in Hobart and Canberra now have much more choice with total listings available to rent close to double the record low levels recorded in September 2018 and around 50% higher than pre-pandemic levels – a factor that has contributed to rental vacancy rates easing in these two cities over the past year.

Renters in Hobart are enjoying more choice following record low supply in recent years. Picture: Supplied

Demand to rent remains elevated in inner-city areas following the return to offices and universities, while supply shortages are set to remain for now.

Strong migration, low vacancy rates and limited new supply means tough conditions for renters are likely to remain.

To address the housing shortage and cater for our growing population, it is key that we continue to focus on building more homes.

Unfortunately, incentivising investors to return to the market is a missing ingredient in the budget.

Homebuying incentives – eligibility expanded but many miss out

The government has also expanded the eligibility criteria for the First Home Guarantee, and the Regional First Home Buyer Guarantee.

The schemes have previously only been available to singles and married or de facto partners, but now the expanded classification of a “couple” includes friends, siblings, and other family members, meaning they will be eligible for joint applications from July 1, 2023.

The guarantees will also be expanded to non first-home buyers who haven’t owned a property in Australia in the past 10 years, supporting those who have fallen out of homeownership, now also including permanent residents.

The Family Home Guarantee will also be expanded to be available to eligible borrowers who are single legal guardians of children such as an aunt, uncle or grandparent, in addition to single natural and adoptive parents.

These changes build on last year’s increase in the number of places available – 35,000 per year for the First Home Guarantees, 10,000 places per year under the Regional First Home Buyer Guarantee, and 5,000 places per year to 30 June 2025 under the Family Home Guarantee.

In the current environment, while home prices in most markets are slightly lower now than they were 12 months ago, borrowing costs are higher and prices have fallen by much less than the calculated shift in borrowing capacities would imply.

Affordability has deteriorated markedly, to the worst levels since the 1990s on some measures, and repayments are now very high relative to history in real terms.

These conditions are challenging for first-home buyers, for whom the most significant hurdle to home ownership is the deposit burden. The expanded Home Guarantee Scheme aims to tackle this issue.

The First Home Guarantee scheme allows an eligible applicant to buy with just a 5% deposit, with the government guaranteeing the remaining 15%.

Expanded homebuying schemes could see more Australians own a home sooner. Picture: Getty

While the time taken to save for a deposit is influenced by many factors, such as your savings rate and how much you can afford to put aside each month towards a deposit, assuming all other variables remain constant, saving for a 5% deposit will take less time.

For example, let’s say you’re buying a home worth $800,000, and you want to save for the deposit. A 20% deposit would be $160,000, and a 5% deposit would be $40,000. That means you would need to save an extra $120,000 for the 20% deposit compared to the 5% deposit.

If you can save $1,000 per month towards the deposit, it would take you 10 years to save $120,000 for the 20% deposit, and 2.5 years to save $40,000 for the 5% deposit. Therefore, you would save 7.5 years by utilising the 5% deposit instead of the 20% deposit.

By reducing how much deposit they must save, and expanding the definition of a “couple” the scheme will help some Australians purchase a home sooner than they otherwise could have.

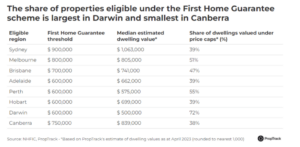

To be eligible for the scheme, the property you buy must fall under a certain price cap.

These price caps will remain a constraint for some first-home buyers because they rule out more than half of homes in some capitals.

Eligible applicants will have plenty of choice in Darwin, Perth and Melbourne but less in Sydney, Hobart and the least in Canberra.

First Home Grant share of eligible homes – Melbourne

Share of all dwellings that fall under price caps, based on PropTrack estimated dwelling values; by SA3

Risks of expanded scheme

The key feature of the scheme is that borrowers are taking out higher loan-to-valuation ratio mortgages. That means price falls of as little as 5% would take the borrower underwater – owing more on their mortgage than their home is worth.

There are risks to taxpayers too. If the borrower was to subsequently default while underwater, losses on mortgages guaranteed by the scheme would be borne by taxpayers.

The substantial interest rate tightening that has been pushed through already saw conditions in the housing market rebalance quickly last year, with prices falling from peak levels in most parts of the country.

Prices nationally fell for nine consecutive months, but that trend has reversed this year with national home prices rising for four consecutive months.

The impact of interest rate rises is being counterbalanced by stronger housing demand and tight supply conditions.

Although home prices have begun to increase again this year, the risk of further price falls remains if the downturn seen for much of last year were to find a second wind, meaning these risks are more elevated than they have been in recent years.

Many will still miss out

The scheme will help some purchase sooner than they otherwise could have, likely increasing demand and therefore prices of certain types of properties soon after.

Though the impact on prices and the housing market is likely to be limited.

First-home buyers accounted for just 16.5% of new lending in March according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

However, the allocation for each guarantee scheme has not increased.

Many first-home buyers will still miss out given the limit of 35,000 places. Over the past 5 years the number of first-home buyers taking out mortgages has averaged more than 120,000 per annum.

And in the past 12 months 102,060 first-home buyers took out mortgages.

The allocation caps will limit the effectiveness of the scheme, but it is also increasing or bringing forward demand for housing without increasing supply to match.

The end result is many who are finding it both hard to buy and increasingly hard to rent will miss out, meaning the benefits of the scheme are a drop in the ocean in resolving housing affordability.

The only long-term solution to housing affordability is to build more of the right homes in the places where people want to live.

Building more homes remains key to improving housing affordability. Picture: iStock

It’s clear what’s missing is a serious plan to reform state and local government planning systems and to increase the supply of new dwellings. Demand-side incentives should be tied to unlocking land, improving planning efficiencies, and boosting new supply.

There is mention that planning ministers, working with the Australian Local Government Association, will develop a proposal for National Cabinet in the next 6 months outlining reforms to increase housing supply and affordability – but no concrete measures are outlined in the budget.

With Australia’s population set to keep growing over the next two decades, building more new homes where people want to live will be critical if we are serious about tackling housing affordability.

Stamp duty reform a missed opportunity?

Deteriorating housing affordability was a key focus of the federal budget, seeking to alleviate some of the pressures both those looking to buy or rent currently face.

But stamp duty reform was not one of them.

Support for the states to transition from stamp duty to a broad-based land tax must be seriously explored if we hope to create a strong structural foundation for an efficient and equitable property market.

Stamp duty reform is needed to allow the property market to function more efficiently in all states.

Some of the issues identified with stamp duties are that they increase the cost of housing, increase the deposit burden and disincentivise household mobility.

Stamp duty is an inefficient tax that acts to slow the property market, reduces economic growth and makes housing less affordable.

The former NSW Treasury estimated that eliminating stamp duty could unlock $10 billion in economic value.

Stamp duty is seen as a barrier to homeownership, but also a disincentive to rightsizing. Picture: Getty

State governments replacing stamp duty with an annual land tax would help to better utilise the available housing stock.

Stamp duty makes it harder for many first-home buyers to buy a home because it is an upfront additional cost on top of the deposit you have to save. In Sydney it takes 7 years to save a 20% deposit for an entry-level home. In Melbourne, it takes a little over 6 years.

Stamp duty adds to this deposit hurdle, including adding an extra year of saving in most cities for a relatively affordable home.

State governments already recognise the impact of stamp duty on first-home buyers; that’s why most states offer stamp duty concessions or waivers for first-home buyers.

Home ownership rates have been declining among younger, lower income Australians for decades. Reducing up front purchase costs for first-home buyers by replacing stamp duty with an annual land tax, would reduce the deposit hurdle for first timers and allow many to purchase sooner.

Stamp duty also discourages rightsizing, with many “empty nest” households not needing as much space as they have. But they keep it because downsizing is unattractive due to the size of transfer costs.

The big barrier here is stamp duty, which adds to the cost of downsizing, promoting inefficient use of existing housing stock.

But stamp duty is also a barrier to moving in general, for example, for a new job.

Reforming stamp duty could not only help younger households and improve housing affordability, but also better utilise Australia’s existing dwelling stock. A clear win in the face of a growing population and existing housing shortage.

Source: realestate.com.au