CoreLogic published a note outlining what we knew about the so-called ‘fixed-rate cliff’ in February this year. It was a forward look into what we could expect when an estimated 1.3 million home loans went from low fixed rates, to high variable rates.

Now, six months later, we’ve arrived at what was forecast as the peak transition period, a three-month duration where the bulk of these loans would expire. August provides us with an understanding of how the housing market is performing amid this critical transition phase and fresh insights on the state of the mortgage market from the RBA and APRA.

This note summarises the state of risk in the housing market, as the majority of fixed term facilities created through COVID expire. There has been a slowdown in economic activity and housing market momentum in response to higher rates across all mortgage holders, and CoreLogic has observed an unusual increase in new listings over the past few weeks. Overall, the risk of arrears and default remains contained within Australia’s large mortgage market and we expect a level of resilience amid tight labour market conditions.

Fixed-rate recap

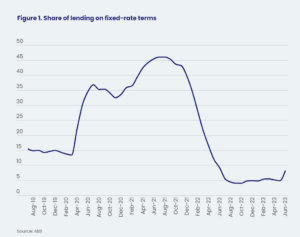

The ‘fixed-rate cliff’ is a term used to describe the expiry of a significantly larger than average number of fixed-term loan facilities, which were secured between mid-2020 and mid-2022. Figure 1 shows the expansion of fixed rate lending early on in the pandemic, which peaked at 46% of secured housing finance in July and August of 2021, compared to pre-COVID levels of 15%. The majority of fixed rate loans are taken out with a term of three years or less, so the biggest number of facilities were expected to expire this year (880,000), followed by another 450,000 next year.

Fixed-rate risk

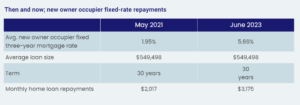

The risk associated with the hundreds of thousands of fixed-rate loan expiries is that some borrowers will struggle to service their loans on the new, higher, variable rates. Average fixed rates with terms of three years or less bottomed out at 1.95% in May 2021 for owner occupiers, while average variable rates for new owner occupier borrowers are now 5.66%. For the average loan size in May of 2021 ($549,498) on a 30-year loan term, this represents an increase in monthly home loan repayments from $2,017 per month to $3,175, or an increase of almost 60%.

The numbers sound big, but perspective is important

The August Statement of Monetary Policy provided further insights around fixed loan term expiries. The statement outlined that the expiry of fixed-rate terms peaked at just under 5.5% of outstanding credit in the June quarter, and remain a low portion of outstanding credit month-to-month.

The surge in fixed-rate fixed borrowing through COVID still only saw fixed lending peak at about 40% of outstanding housing credit in early 2022. Figure 1 shows new lending has since returned to largely variable terms. This means a vast, and increasing majority of housing debt, is on variable rates. In contrast to fixed-rate mortgage holders, variable rate borrowers have already been exposed to the majority of cash rate rises. Based on average outstanding lending rates, an estimated 80% of the 400-basis point increase as of June. While variable-rate mortgage holders have been feeling the pinch of rate rises and high cost of living pressures, official data suggests arrears remain in check and are still below pre-pandemic levels, and rising home values since February has likely only further reduced the incidence of loans in negative equity.

Official data suggests risks remain contained

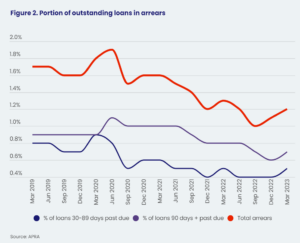

The latest quarterly publication from APRA shows housing credit in arrears is extremely low at 1.2% of outstanding debt, where ‘arrears’ means payments are late. Non-performing credit, which is late payments of 90 days or more, made up 0.7% of all mortgages in the March quarter of this year, while payments just starting to be late – between 30 and 89 days – were even less at 0.5%. Although total housing repayments in arrears has increased from a recent low of 1.0% in the September quarter of 2022, but remained below pre-pandemic levels at 1.6% in the March quarter (Figure 2).

Although late repayments make up a small part of outstanding housing credit, this is not necessarily a timely measure of mortgage stress. Not only is the APRA data slightly lagged (June quarter data will be available in early September), but measuring late payments means there is an additional lag on the data, where those struggling with higher housing costs tend to prioritise housing payments, and may take a while to actually miss a payment. At recent parliamentary hearings in July, major bank representatives have continued to espouse the resilience of home loan borrowers and the low portion of late payments.

Economic and housing data suggests interest rate rises are having an impact

As increased housing costs alongside high cost of living expenses continue to hit borrowers, the pressure is being reflected in economic data. The Westpac-Mi consumer sentiment index – measuring the change in the level of consumer confidence in economic activity – slipped -0.4% in August from already low levels, led by a -7.2% dip across mortgage holders. The RBA has also reported extra payments into offset and redraw facilities – which were trending ever higher during COVID – are now easing, as more money for housing costs is diverted to interest payments. This figure aligns with a reduction in the household savings ratio to 3.5%, and there was also a -0.5% fall in the volume of retail spending fell in the June quarter.

Housing metrics are also showing some weakness, following a recovery trend through the first half of the year. The pace of increase in the CoreLogic Home Value Index has slowed from 1.1% in June to 0.6% in July, and the clearance rate to the end of July had also trended slightly lower, averaging 66.5% compared to 71.3% at the end of May.

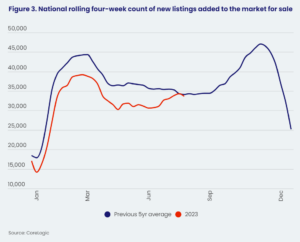

Interestingly, CoreLogic new listing counts increased 2.8%, or by around 912 listings, through July. This was an unusual trend, because new listings have historically trended lower through July, amid a seasonal winter slowdown. For the past five years, new listings have moved -3.6% lower from June to July (Figure 3). The trend has been especially notable in Sydney where new listings have moved 7.6% higher through the month, and in Melbourne where new listings moved 8.6% higher.

The rise in new listings could be at least partially attributed to more motivated selling if home owners are struggling to keep up with rising mortgage repayments. It could even be indicative of some homeowners selling based on foreseen issues with mortgage serviceability, with a sizable number of expiring fixed-term facilities toward the end of this year.

However, there could be other reasons for an out-of-season uplift in new listings. As we have noted previously, new listings activity has often been led by a rise in home values and better selling conditions, with a every 1% increase in home values annually translating to an average uplift of half a percent in new listings. With home values rising for the past five months, this may be prompting more selling decisions that did not take place when the market was in decline last spring. Some prospective sellers may also be looking to get ahead of the spring selling season when competition among vendors is likely to be more intense, a tactic which has been noted in liaison with some real estate agencies.

The addition of new listings to the market are not necessarily a sign that higher mortgage costs are creating forced selling conditions. However, as more mortgage holders are exposed to higher interest costs, it will be a telling metric to follow.

Edge of an abyss or gentle decline?

Overall, it seems official data on mortgage stress has not seen a blow out in arrears amid the expiry of low fixed-term loans. As home values rise, the risk of default also remains low. However, as what is likely to be the last of the RBA’s rate hikes is passed through to households with a mortgage, there may be a mild deterioration in housing market conditions if new listings decisions continue to rise. The good news for mortgage holders is that this period of economic slowdown will also take the RBA closer to its long term inflation target, which could be the impetus for a reduction in the cash rate in the second half of 2024, as predicted by most major banks.

Source: corelogic.com.au