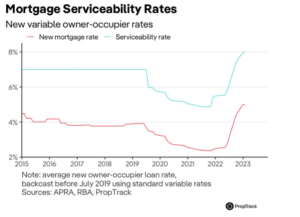

The serviceability buffer is a key regulatory setting that impacts how much Australians can borrow, and therefore what happens to home prices.

In late February, APRA left the buffer unchanged at 3 percentage points (ppt).

But many – particularly lenders – have called for it to be reduced.

It’s worth looking at the data to understand what that would mean for borrower resilience. Because it matters: a 0.5ppt decrease increases borrowing capacities by around 5%

The serviceability buffer ensures financial resilience from interest rate increases

The serviceability buffer is the amount lenders add to current mortgage rates before assessing how much to lend a borrower.

Currently, new owner occupiers facing interest rates of around 5.5% must be able to afford to repay a loan if interest rates increased to 8.5%.

The serviceability buffer is designed to insulate borrowers from interest rate risk. If interest rates go up, borrowers should be able to afford to repay the loan as long as the increase is less than the buffer.

If there were no buffer, any interest rate increase would push anyone who borrowed the maximum offered into a position where they could no longer afford to make repayments.

But it is worth remembering that very few borrowers borrow their maximum – around 10% according to CBA – so most have even more resilience than described simply by the minimum buffers.

A simple change by APRA could ease some of the pain of rising rates – but is it worth it? Picture: Getty

The buffer and other serviceability settings have been tweaked extensively

A rough recent history of the buffer and related measures is:

- December 2014: APRA standardised serviceability assessments to require a minimum 2 ppt buffer and 7% floor (a minimum serviceability rate regardless of the current interest rate)

- July 2019: the floor was removed, and the buffer increased to 2.5ppt

- November 2021: the buffer increased to 3 ppt

Over much of the past decade, the 7% floor rate was binding, meaning interest rate changes did not change borrowing capacities.

But with interest rates persistently below that level: “the gap between the 7 per cent floor and actual rates paid has become quite wide in some cases – possibly unnecessarily so” according to APRA.

In other words, the amount of resilience built into mortgages was too large and imposed a large cost in terms of restricting borrowing and locking people out of the housing market.

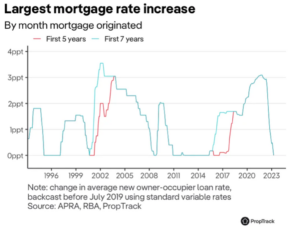

The current buffer covers around 95% of historical interest rate increases

The buffer protects against interest rate risk, or interest rates increasing after a borrower has taken out a loan.

No buffer can eliminate all interest rate risk since interest rates can increase indefinitely.

But the first 5 or 7 years of a loan are when borrowers are most susceptible to interest rate increases. This is because after this point they have generally seen their income and equity increase enough to significantly reduce the burden of mortgage repayments.

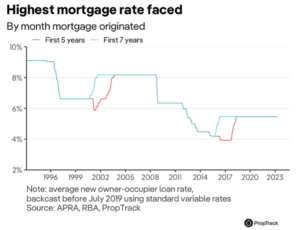

It is rare for borrowers to face mortgage rates 3ppts above their initial rate. Such increases have only occurred for loans taken out from 2001 to 2003 (when it almost only affected loans more than 5 years old) and – very saliently – for loans taken out in 2021.

Quantifying this interest rate risk, 95% of interest rate increases over the first 7 years of a loans life were less than 3.05ppt. This covers the last 30 years, since the RBA has been targeting inflation with interest rates.

This is almost exactly the current level of the buffer: 3ppt.

Alternatively, if you were only concerned with risks over the first 5 years of mortgages, 95% of increases are less than 2.92ppt. Not too dissimilar.

Higher interest rates over the remainder of 2023 will shift these distributions up slightly. But 3ppt seems about right to insulate borrowers from around 95% of historical interest rate risk.

Lowering the buffer to 2.5ppt – its level before late 2021 – would cover only around 80% of historical interest rate increases for borrowers over the first 7 years, and 90% over the first 5 years.

Before making any change to the buffer, APRA will need to decide if this level of resilience is sufficient.

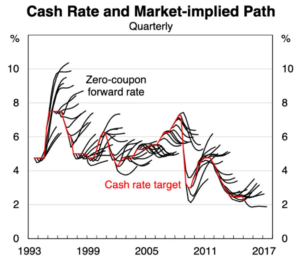

It would be impractical to adjust the buffer based on expected interest rates

It seems intuitive that since interest rates have increased sharply, the buffer does not need to be as large now. Alternatively, it is less likely rates will increase another 3ppt from now so the buffer can be reduced.

Similarly, when rates were low they were more likely to ‘normalise’ or increase. This was, broadly speaking, the motivation behind the minimum serviceability rate or floor of 7% which prevailed before 2019.

These ideas suggest the buffer should change based on the current level of interest rates. However, operationalizing this is practically difficult.

APRA would require accurate forecasts of interest rates. But financial markets have been shown to have large forecasting errors.

And the reintroduction of a floor rate would require APRA to have a view on the ‘normal’ level of mortgage rates – something considered extremely difficult to tie down, and which estimates suggest have changed markedly over the past. In practice, lenders continue to use floor rates, so APRA would need to have strong evidence that these are not being set high enough.

Buffer settings could not change as quickly as interest rate forecasts, which often adjust substantially over a short period of time. And perhaps more importantly, if these forecasts are wrong, borrowers may be left with reduced resilience.

These are the arguments for a well analytically defined buffer that is constant throughout the economic cycle.

The buffer cannot account for inflation or income loss

APRA has stated that serviceability should account for more than just interest rate risk: “The buffer provides an important contingency not only for rises in interest rates over the life of the loan, but also for any unforeseen changes in a borrower’s income or expenses”.

In practice any spare cashflow, such as that provided by the buffer, can protect against these shocks, but the buffer cannot be calibrated to account for these risks.

No loan is written to withstand significant income falls, such as job loss, and nor should it: the result would be no lending at all.

And incorporating inflation into the calculation of the buffer would lead to smaller not larger buffers – since income growth exceeds expenses inflation most of the time (although current conditions are a clear counter-example).

It remains to be seen if the buffer will be reduced

APRA will need to judge if reducing the buffer to 2.5ppt – and enabling 5% higher borrowing capacities – is worth reducing the resilience of future borrowers from 95% of historical interest rate risk to 80-90%.

However, adjusting the buffer based on expected interest rate movements is likely to be difficult in practice and would require an ongoing discussion, and adjustment of the right serviceability settings. But such settings are not designed to be changed quickly – for one it would add uncertainty for lenders and borrowers throughout the purchasing journey.

It also places a lot of pressure on getting interest rate forecasts right, so borrowers aren’t left with insufficient buffers right when they need it most.

Source: Realestate.com.au